No serious collector of 19th century fiction can be unaware of the preponderance of novels originally published in three volumes. The so called 'three deckers', now relatively scarce and hence often prohibitively expensive, were once the staple reading of whole swathes of the newly emerging middle class. But they did not buy them; they were borrowed, a volume at a time from one of the circulating libraries and, more likely than not from one of those run by Charles Edward Mudie (1818-1890).

From the 1840's to the 1890's Mudie's Select Library determined the reading habits of two generations of readers. Such was Mudie's power that an author's career probably depended on his or hers work being selected by the library. Confident that Mudie would take the book, publishers could then print runs of the work in their thousands, with a very high percentage going straight to Mudie's library at a discount price. Subscribers to the library, at a cost of one guinea per year, could then borrow a volume at a time. This arrangement suited authors, publishers and readers.

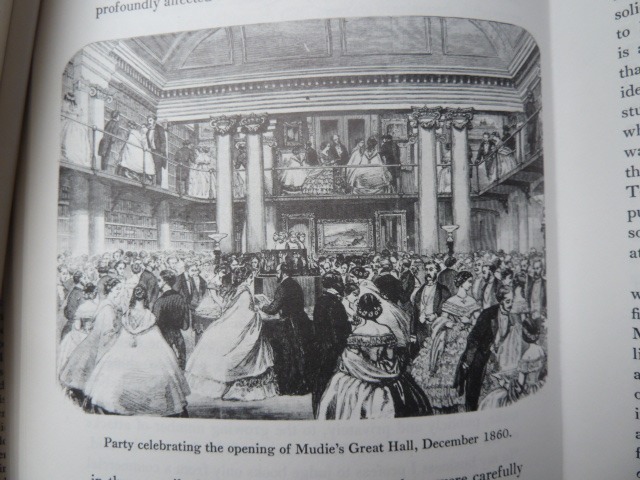

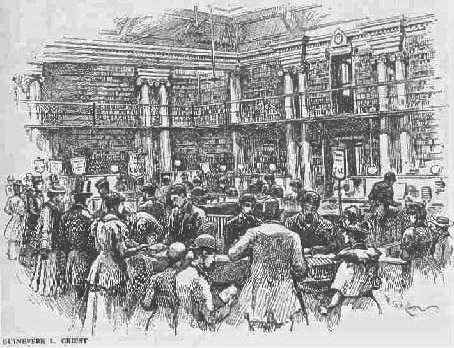

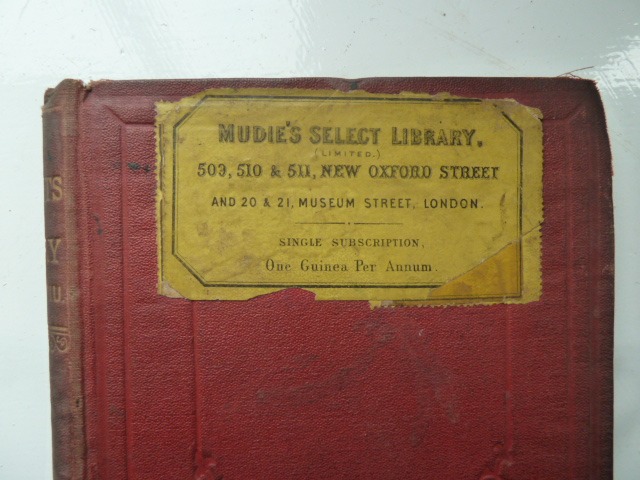

In London, readers flocked to Mudie's massive emporium on New Oxford Street, where armies of employees would rapidly find the desired volumes selected from Mudie's list.

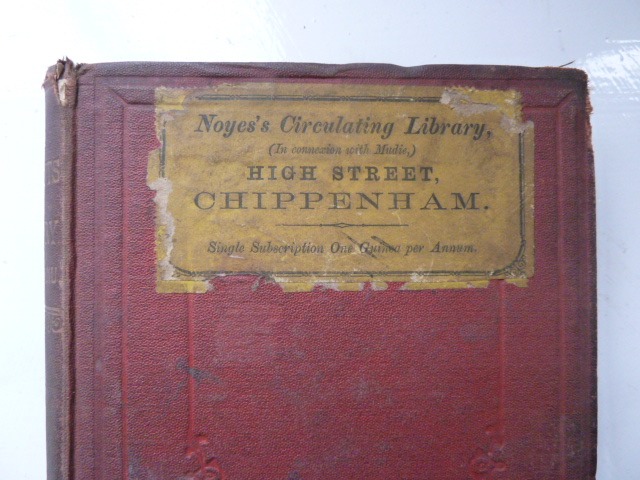

In the large provincial towns there were more branches of Mudie, who also supplied books to local independent circulating libraries, where the same arrangements applied.

It was possible to purchase three deckers from Mudie, but they were very expensive and only the wealthy would have been able to add them to their private collections. Typically, the work would appear in a cheap single volume edition a year or so after first publication in three volumes. The genius of Mudie's modus operandi was that essentially three subscribers would be reading one book at the same time; hence three times the profit. He could also negotiate massive discounts with the publishers given the quantities he ordered; he took 500 copies of the first edition of Darwin's 'Origin of Species' and 3,000 sets of the 3 volume 'Mill on the Floss' by George Eliot, though a typical order for an established writer would be 1,500 sets.

There were dissenting voices. Many argued that the straitjacket of three volumes led to over-long novels full of irrelevant sub-plots; conversely it was argued that the luxury of three volumes allowed generous margins and large font sizes essential for the elderly reader. Also Mudie, being a deeply religious man, appled selection criteria to his library that eliminated all books except those that could be 'safely read to the servants'. As the century neared its end the clamour for change was irrestistible; from authors, eager to try out new forms of shorter novel and frustrated by Mudie's arbitrary censorship, publishers keen to break Mudie's near monopoly and, perhaps most compellingly, from the new free public libraries springing up all over Britain.

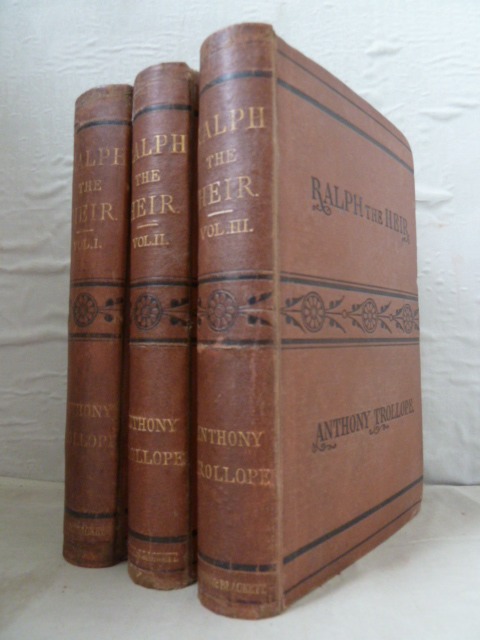

In 1894, Mudie and his great contemporary competitor W H Smith agreed to end the three volume format and almost immediately, as a publishing form, it disappeared. From this time almost all novels first appeared in single volume editions; more rarely in two volumes. However, today, amongst the most desirable of nineteenth century books for the collector are the great three volume first editions of writers such as Thomas Hardy, J Sheridan Le Fanu and Anthony Trollope. Since these were borrowed in profusion, copies in fine condition are extremely scarce.

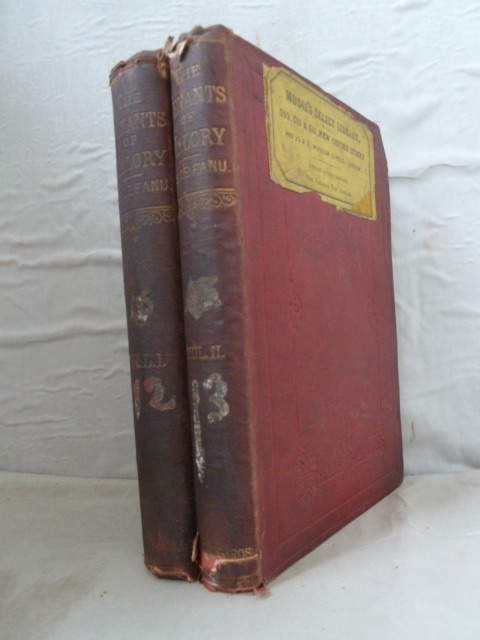

The High Barn Library has only one or two direct links back to Mudie. Volumes 1 and 2 (only) of a three volume set of Le Fanu's 'The Tenants of Malory' respectively bear on their front boards the distinctive yellow labels of Mudie's New Oxford Street Select Library and of Noyes's Circulating Library at Chippenham, supplied by Mudie.

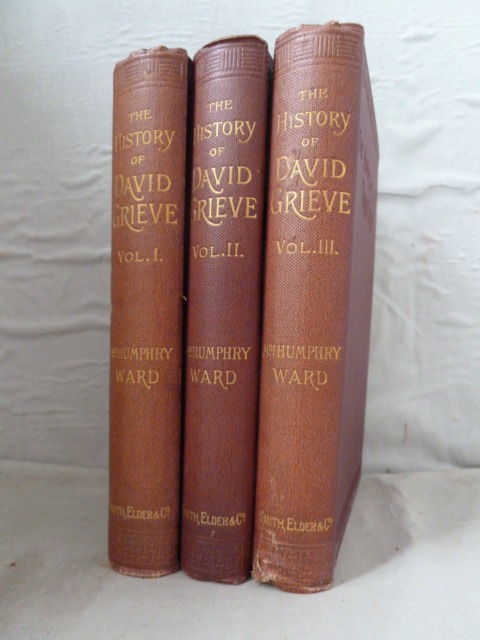

The fate of Volume 3 is unknown. These date from 1867, when Mudie's power was at its height. However, there are two other complete three deckers on our shelves: Anthony Trollope's 'Ralph the Heir' (1871) and Mrs Ward's 'The History of David Grieve' dating from 1894 right at the end of Mudie's dominance.

The firm of Mudie continued into the 1930s but at a much reduced level, finally closing its doors shortly before the Second World War. However, W H Smith, who had established a monopoly on railway book stalls (rashly spurned by Mudie) in the mid nineteenth century, continue as a major book seller, but not, as originally, a lending library.

Subscription libraries had originated well before Mudie entered the scene, certainly by the early eighteenth century, but it was the sheer scale of Mudie's operations from the 1840s on that drove most competitors out of business. In the 1860s, for example, Mudie was increasing his stock at the rate of 170,000 volumes a year. It was estimated that Mudie's patrons comprised about half of the total number of families sufficiently educated to enjoy novel reading. Mudie's list did contain all types of reading matter - history, science, travel, theology, for example - but over no field did he exercise such absolute control as novel writing, and, from an artistic point of view, it can only be hoped that this level of control is not repeated in the future.

A wonderful history of Mudie's Circulating Library is contained in the study 'Mudie's Circulating Library & the Victorian Novel' by Guinevere L Girest (David & Charles, 1970). It makes fascinating reading and throws great light on many aspects of Victorian authors and their works. I am sure that, had Mudie demanded four voulmes per novel, we would now be enjoying Anthony Trollopes's 'The Four Clerks' rather than 'The Three Clerks', whose adventures so conveniently fall into three volumes.

- Posted using BlogPress from my iPad